On April 23, 2022, my mother-in-law, Hella Meewis Beuck, died, and the world stopped.

Or it should have. Where my bio-mother was largely emotionally absent, Mutti (mama in German), was present with her whole heart. She knew how to listen, how to comfort, and how to work alongside without taking over. Whenever she came to visit us, she brought her work pants so she could garden with me. “But you, Janette, are chief,” she’d say. “I do what you want.”

I’m someone who cherishes alone time, and need a lot of it in order to be healthy. And yet, when Mutti stayed her with us, for weeks at a time, I wished she would stay forever.

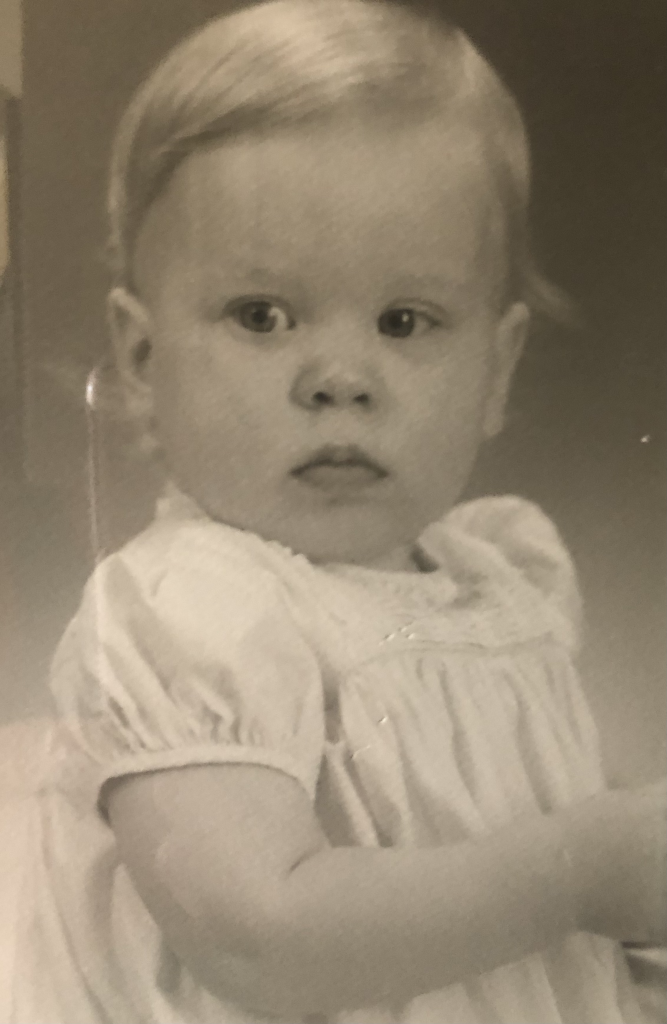

I met her on my first trip to northern Germany with Birte in 2002. She opened her arms and her home to me, eagerly showing me old photo albums of when Birte was young, and feeding us her lovely homemade concoctions. The Germans really do have the best bread, and it’s amazing how many delicious meals can be made with potatoes and cabbage. And the asparagus in Spring cannot be rivaled.

The first time she came to visit us here, we lived in Oakland. Birte’s father, Gerhard, came too; we showed them all around the Bay Area, then took them to Mendocino, one of our favorite places, where we stayed in a gorgeous house on a cliff above the wild Pacific.

Mutti came to our Northern California home again again when we got married in 2007, along with Birte’s brother, Lars, and his daughter Jenny, who has so much of Mutti in her. (Had my own mother still been alive, she would not have come to our wedding, even though she did not live so far away; she had refused upon meeting Birte to even shake her proffered hand. Nor did my sister, aunt, or favorite cousin come to the wedding, all citing evangelical dogma as their excuse. My father, brother, and their wives did attend, however; and for that we were grateful.)

But the last two times Mutti visited us, she came on her own. On the days Birte worked, and Mutti and I were alone together, I came to know her loving, generous spirit best. We talked, laughed, told each other stories, worked in the garden, and sat quietly together, reading or writing.

It’s not always easy traveling with another person, but I’d travel with her any day. We took her to the Grand Canyon and Sedona, Big Sur, Asilomar, and Murphy’s.

On that first trip to the Grand Canyon, Birte named us Hellie Eins and Hellie Swei (Hellie One and Hellie Two). We each deferred to each other to the point of it being comical (You go first! No, you!), and we laughed at ourselves for that. We shared so many other traits, too; it was as if we were related. And we were, in our souls.

Our first early morning at the Grant Canyon, Mutti whispered, “Is it okay if I get up?” We were all in one small room, with two queen beds. Birte said, “You don’t have to ask our permission.” Mutti was often bullied at home by her husband, so it took a while for her to come into her own with us. But once she was fully herself and no longer being so careful, she blossomed into the gorgeous, playful, funny, smart woman, we knew she was; and we had a ball.

One freezing cold morning on that trip, we went to the Canyon before dawn to watch the sunrise. While Birte and I complained about the cold and wanted to quit before our massive star began its appearance, she insisted we stay, cheerful and uncomplaining. B and I jogged in place, jumped up and down, and ran short sprints in an effort to increase our body temperatures. I wrapped my entire face in my scarf, with only one eye looking out: Cyclops. Mutti walked quietly, uncomplaining.

We have visited the family in northern Germany once a year or so, for the past 21 years we’ve been together. Each time, when we first arrived, Mutti (usually with Lars and one or more of his kids) greeted us at the airport with two roses, one for each of us. She brought us water and food, and settled us into our apartment with extra dish towels, egg-free cookies and cakes, shopping bags, and rubber bands. She showered us with her time and love, in spite of how busy she was: managing her own home and husband, and also being deeply involved in the lives of Birte’s three siblings and their combined eight children (now nine).

She helped raise our niece Jenny, who now displays so many of Mutti’s best qualities: her hospitality, her generosity, her ability to listen and really hear.

The second time Mutti visited us, she began having severe pain in one leg. This, unbeknownst to us, was the beginning of her physical decline. On April 23, 2022, she died of heart disease, her beautiful heart so deeply broken and yet loving to the end. And the world should have ended. But it didn’t.

I still talk with her almost every day, telling her how we’re doing, or asking her for advice on how to deal with my health challenges. My goal is to channel her loving, listening spirit. Each day, I see her in Birte as well: patient, helpful, loving.

I only wish I could hug her one more time, or hear her delightful laugh in response to my fumbling German. You may be gone from this planet, dear Mutti, but you will never be gone from us. You are in us.